Jean-Bertrand Aristide

Saint Juan

Bosco

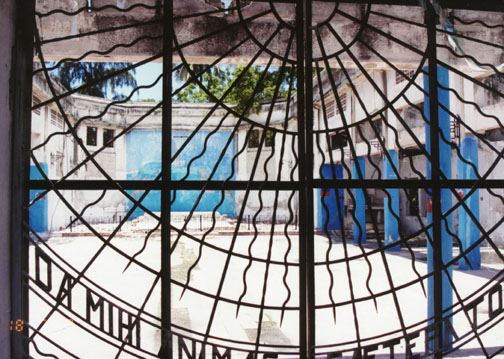

Aristide's Parish church in 1988

the burned

out shell after the September 11, 1988

massacre by the Tonton Macoute and Haitian military

Internationally supervised elections in December 1990 resulted in a landslide presidential victory for Jean-Bertrand Aristide, a Roman Catholic priest and an outspoken advocate for the poor. After the army crushed a mutiny led by former officials of the Duvalier regime, Aristide was inaugurated in February 1991.

the national palace

He was ousted by a military coup the following September and went into exile in the United States.

mural commemorating the main tragic events during the military coup

The OAS imposed sanctions on the new military regime, but negotiations for Aristide’s return to office moved slowly. Of the thousands of Haitians who attempted to flee to the United States, more than half were sent back to Haiti by the U.S. Coast Guard. The UN imposed sanctions in June 1993, then suspended them in August after the Haitian military and Aristide agreed on a plan for his reinstatement as head of a democratic government by October 30.

commemorating

the 27 people killed two days after Christmas 1993

when twelve hundred homes were destroyed by the military

in Cite Soleil ,a slum area.

The military government, led by Lieutenant General Raoul Cédras, refused to step down and the UN reimposed sanctions in mid-October. In December, Aristide’s prime minister and chief negotiator in Haiti, Robert Malval, resigned. Gasoline and oil shortages caused by UN sanctions left relief organizations unable to deliver food and medical supplies, although fuel was being successfully smuggled into Haiti from the Dominican Republic.

remnants

of Fort Dimanche

infamous torture prison of the Duvalier dictatorship

(dismantled in 1994 after Aristide returned)

In May 1994 the UN imposed broader sanctions, including a ban on international air travel, against Haiti’s military rulers. The new sanctions, aimed at forcing them to step down and allow Aristide to return to power, permitted only food and medicine to be shipped into Haiti. In response to economic conditions worsened by sanctions and continued repression by the military, the number of Haitians fleeing the country and seeking political asylum in the United States greatly increased. An additional 20,000 refugees attempted to reach the United States in 1994. The UN passed a resolution that authorized member states to use all necessary means to facilitate the return of Aristide.

former

military building

(where the September 1994 meeting took place)

On September 16, 1994, the United States dispatched former President Jimmy Carter, Senator Sam Nunn, and former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Colin Powell for talks with Haiti’s military leadership. Facing the threat of a U.S. invasion, the Cédras regime agreed to turn over power to President Aristide. Under the agreement General Cédras, General Philippe Biamby, and Chief of Police Lieutenant Colonel Michel François would retire and their positions would be filled with rightfully appointed individuals. In return the U.S. negotiators guaranteed that the embargo on Haiti would be lifted.

the cemetery where many victims of the coup were buried

On September 19, a force of 20,000 U.S. troops arrived in Haiti to oversee the transition from dictatorship to democracy. The troops helped ensure a secure environment throughout the country by seizing weapons and arresting former members of the police paramilitary. Generals Cédras and Biamby were offered exile in Panama and they departed the country in October; François left for the Dominican Republic.

On

September 11, 1993, the fifth anniversary of the Saint Bosco massacre

Antwan Izmery, a friend and supporter of Aristide,

was taken from mass at Sacre Couer and gunned down in this street.

Ron Voss, cleaning the stature to his martyred friend, Antwan Izmery

The UN lifted its embargo in late September and President Aristide returned to Haiti on October 15, 1994. In November he named his former commerce minister, Smarck Michel, as the new prime minister. In keeping with Roman Catholic regulations that priests not hold public office, Aristide submitted his request to leave the priesthood that same month.

Three

weeks before U.S. led intervention

Father Jean Marie Vincent, leader of one of the peasant organizations,

was murdered at the front gate of the Montfort priests' home.

Aristide’s return raised the hopes of many Haitians for peace, reconciliation, and economic revival. Haiti’s economy, never very stable, was weakened to the point of collapse by the military takeover and subsequent international embargo. Much of Haiti’s infrastructure—including port facilities, bridges, and roadways—had deteriorated. Millions of dollars in international aid was earmarked for the improvement and stabilization of Haiti, including the disbanding of the nation’s police and military and the recruiting, training, and deployment of new members. As part of the effort, Aristide ordered the forced retirement of 43 senior army officers in February 1995, including all of the generals and lieutenants who had served under the military government that overthrew Aristide in 1991. In early 1995 U.S. forces left Haiti and a UN peacekeeping contingent took over.

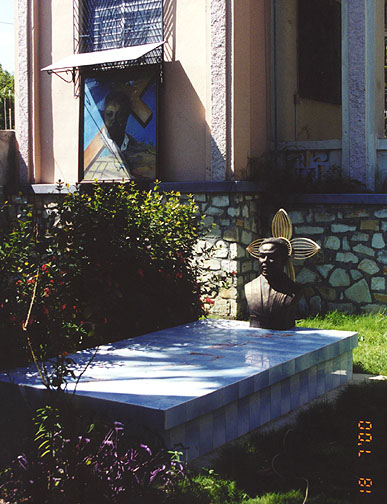

monument to those who suffered during the military coup

Haiti staged general elections in June 1995 in which more than 10,000 candidates ran for 18 of 27 Senate seats, all 83 seats in the Chamber of Deputies, 134 mayoral posts, and positions in 565 local councils. The elections were an important test for the fledgling civilian government and about half of the country’s 3.5 million registered voters cast ballots. International election observers and news outlets reported that the elections were peaceful, but also marked by chaos, confusion, and widespread violations of election procedures, including unopened ballots, poor ballot distribution, and lack of information for voters. Makeup elections were held in August for people unable to vote in June, or for those areas where votes had not been counted because of administrative problems. The Lavalas Platform, a three-party coalition endorsed by Aristide, dominated both elections, winning over two-thirds of the legislative races and three-fourths of the mayoral elections.

In October 1995 Prime Minister Michel resigned after clashes with Aristide and other government officials over Michel’s support for economic reforms backed by the United States, including the privatization of state-owned companies such as electric and telephone utilities, banks, and the country’s main port. The next month the United States suspended $4.5 million in economic aid, citing delays by Aristide’s government in implementing the economic reforms.

In December 1995 Aristide’s close friend and handpicked successor René Preval was elected president of Haiti in a landslide victory. Preval had been Aristide’s prime minister at the time of the 1991 coup. Although Aristide was constitutionally forbidden to run for a second consecutive presidential term, many Haitians argued that he should have been able to make up for the three years he spent in exile by serving another three years in office. Uncertainty surrounding the transfer of power, including statements by Aristide hinting that he might not step down, led the United States to pressure Aristide to reaffirm his pledge to a smooth transfer of power.

After a wave of violence and political assassinations, President-elect Preval asked the UN in January 1996 to keep between 1000 and 1500 UN troops in Haiti for an additional six months. The 5800-member UN force had been scheduled to leave at the end of February. Preval was inaugurated as president of Haiti on February 7, 1996. In his last official act as president, Aristide restored Haiti’s diplomatic relations with Cuba, which had been broken off in 1961 under diplomatic pressure from the United States. Rosny Smarth, an agronomist and member of the ruling Lavalas Platform, was selected as Haiti’s new prime minister on March 6, 1996, becoming the country’s third prime minister in less than a year.

The last U.S. combat units left Haiti at the end of April 1996, just as the United States froze about half of its economic aid to the country until the Haitian government could show progress in solving a series of murders of public figures. Haitian officials complained that the United States was asking too much of the country’s recently assembled and inexperienced police force, and that U.S. intelligence agencies were not cooperating with the criminal investigations.

Smarth announced his resignation as prime minister in June 1997, after several months of strikes and protests against government austerity measures. Smarth had been criticized by Aristide and others for following economic policies that aimed to reduce government spending and privatize state-owned industries. Austerity measures were required by international lending agencies as a condition for Haiti to continue receiving needed foreign aid. Smarth’s critics contended that the poverty of Haiti requires government action to relieve the suffering of the poorest members of society.

Following Smarth’s resignation, government reached a standstill that lasted into 1998, as Haiti’s Senate refused to approve candidates for prime minister nominated by Preval. The last UN peacekeeping troops left the island in December 1997, but Haiti’s government remained in a state of disarray as a legislature divided into political factions was unable to approve government budgets or authorize the distribution of foreign aid. In March 1999 Préval appointed a new government by decree, with former education minister Jacques-Edouard Alexis as prime minister.

Parliamentary and local elections in June 2000, resulted in large majorities for Fanmi Lavalas.

Text from Microsoft Encarta

![]()

![]()